Yesterday we discovered that for 13 euro each, we could see both Ín Flanders Fields and the Yeper Museums, so Bob and I purchased the tickets to both: that for the latter was valid for three days, such a bonus!

As with ‘In Flander’s Fields’ Museum, this too was situated in the old cloth hall.

After yesterday’s emotional experience, this museum was a much more light hearted affair as it covered the history of the township through a variety of mediums with some humour thrown in.

During the Middle Ages, cats were believed to be the physical form of evil spirits and as such were persecuted and murdered. The townsfolk of Ieper still celebrate the Festival of the Cats every three years, but unlike in centuries past today cats are remembered.

There is even a golden jester holding a cat set atop the cloth hall.

Some of the most interesting items were the old brooches.

We liked the focus placed on the people themselves

and the videos.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LU7mXBLrMEU&feature=youtu.be

Bob had a bit of fun in the old courtroom.

We even had our photos taken the old fashioned way.

Museum tour complete, it was time to complete our ride around Ieper.

There was a unique rendition of Christ in the main church,

and the old fish market

with the toll house a few hundred metres to the south of it.

There was the Lille gate for vehicles

and another for the walkers.

Just to the left of the gate above was one of the township’s war cemeteries.

The finishing touches add to a township’s identity.

Last stop for the day was the Last Post ceremony at the Menin Gate.

One of the most renowned Commonwealth war memorials, the current Menin Gate incorporates the ruins of the original that was destroyed during the Great War. It was beneath this, that thousands of men – including Australians – passed on their way to the front lines, not to return.

Sculptured from calcareous blue stone created from ossified marine creatures, the Menin Gate Lions each weigh 1.5 tonnes. In 1936, as acknowledgement of the Australian Great War sacrifice – some 13,000 men – and recognition of friendship, the Burgomeister of Ieper presented the original lions to the Australian government. Today they stand at the War Memorial in Canberra, whilst replicas stand at the Menin Gate entrance.

In return, 1938 saw the Australian War Memorial presenting a bronze statue of the Digger by C. Web Gilbert to the city of Ieper.

On it reads the inscription:

‘In assurance of a friendship that will not be forgotten even when the last digger has gone west and the last grave is crumbled.’

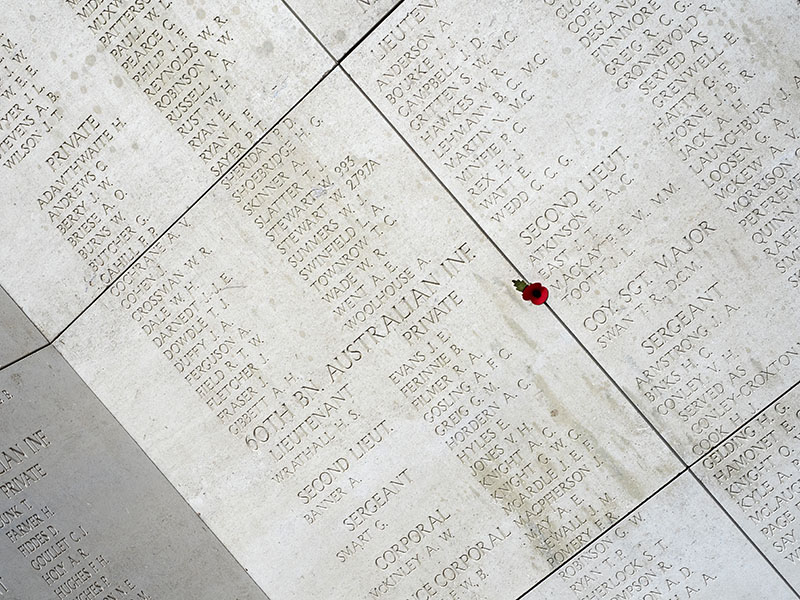

Of the 193,000 Commonwealth soldiers who lost their lives, the majority have no recognised grave site. On the walls of this memorial are scribed the names of 54,896 soldiers who were declared missing between the commencement of war in 1915 and the 15th August, 1917.

All five Australian divisions that consisted of 60 battalions fought at Ieper. At the Menin Gate the visitor will find in excess of 6,000 Australian names: the Aussie men who to this day remain missing in action.

Despite its size, the gate still wasn’t large enough to cater for the names of the remaining 35,000 who went missing between 16th August 1917 and War’s end. These are found at the Tyne Cot, Passendale, Memorial.

Each evening at 8pm, people gather to hear the sounding of the Last Post.

It’s not often that people stand immobile and silent: it happened here. Commencing with the sounding of the first of the posts, this was a haunting service. Interspersed with the pure voices of children’s choirs, whilst a chosen few walked the short distance required to place wreaths in memory, one could have heard a pin drop as the sound of the horns faded in the still night air at the completion of the final sounding. A good ten seconds or more passed before the low hum of voices came to life, filling the void left by this most poignant of ceremonies.

A Little Ieper History

Although inhabited for in excess of one hundred thousand years by tribes such as the Belgae and Celtic Menapians, commencing with the invasion of Rome in 58BC, the history of Ieper since has been one in which battles for possession of the township have been fought time and time again: Romans, Franks, Vikings, English, Gent, Burgandians, Hapsburgs, Spanish, French, Austrians, Dutch…….

The Romans noted the bravery of the early Belgian people’s, but this sadly was observed to be their downfall, as the invaders eliminated all bar a few for their trouble. This in turn proved disadvantageous for the Romans since, with the early peoples eliminated, the scene had been set for waves of invasions from the region that was then known as Magna Germany.

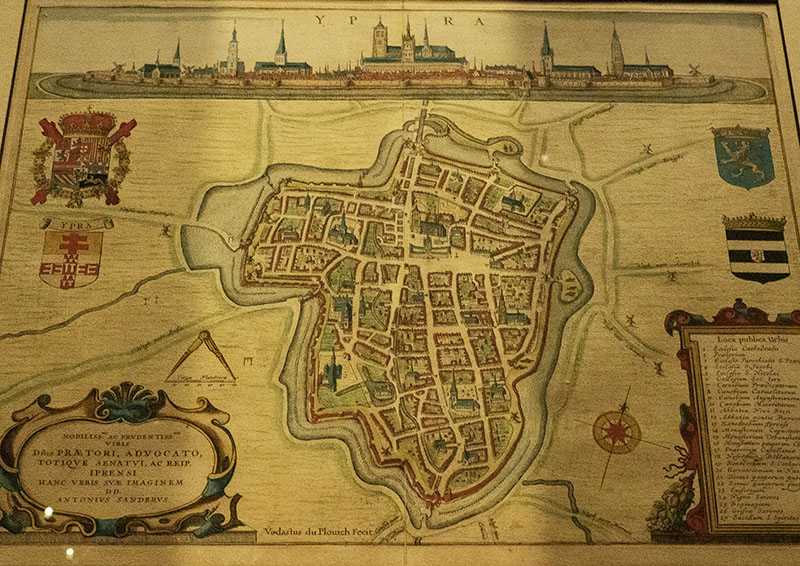

The name by which this interesting township is known today was first recorded in the year 1066, and interestingly, this was also the year that good old William the Conqueror defeated the English at the Battle of Hastings and was crowned king of England.

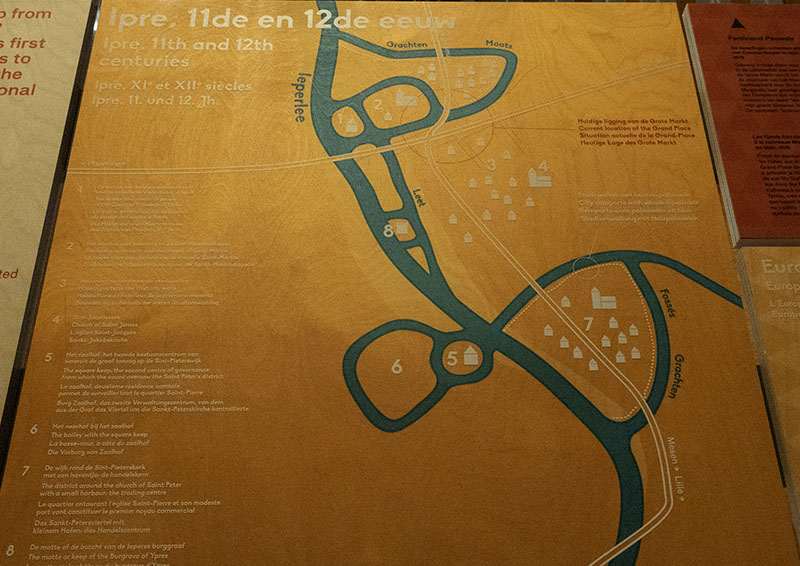

At the time that written history as we know it commenced, the hamlet was a tiny farming settlement situated on the eastern banks of a stream that had its beginnings in the Kemmelburg Ranges in the south.

Situated upon the highest hilltop, not far from where the Grote Mark and St Martins Cathedral stand today, was accomodation for the inhabitants and it was here that the farming was done. Down below, the section between river and settlement consisted of marshland and this was where the animals grazed in relative peace: we mustn’t forget that wolves and small hunting cats were still plentiful during this epoch.

By the eleventh century, technology had advanced to such a degree that the locals had the means for significantly altering the flow of the River Iepere, thereby incorporating it into their defence system: this measure also enabled the traders who owned smaller boats to moor in town. After this, the river in Ieper also became known as ‘Ieperleet’ (river that was modified), then later the ‘Ieperlee’.

Positioned at a junction of roads, canals and various waterways, Ieper became an important trading post, and this meant the township was attacked and conquered numerous times over the centuries. The rebuilding of the township time after time shows the tenacity of the region’s peoples and their love they hold for their town. Despite this, by the 1100s its peoples had built a city of riches, in both economics and culture, from its wool trading with England. With the growth of the cloth trade, it was in the 13th century that construction of the impressive the cloth hall – Lakenhalle – commenced. Taking one century to complete, including repairing damage caused by a town fire, the structure was eventually made of stone.

With the increase in demand for lace and cloth from Ieper,

came the need for a larger waterway that could cope with the increase of boat traffic upon it. The result was Kanaal Ieper – Ijzer that connected this important hub directly to the sea, and up until 1686 passage right into the centre of town.

Initially surrounded by dirt mounds, then dirt mounds with gates of stone for protection, by the end of the 950’s a fortified castle had taken their place. Moving to the early 14th century, the defence system was extended outwards with the addition of an inner and outer moat system that encompassed the settlements that had outgrown the earlier structure.

The mid 14th century was the time of both the Black Death and numerous sieges, and this brought with them economic disaster that lasted several centuries for the city.

Under the Burgundians, a decade long venture saw the construction of an outer stone wall standing almost five metres in height, into which a total of nine gates were incorporated. Of these, with some adjustments along the way, only the Lille Gate remains from the time period of 1385. The 1600s, found the Spanish, then French, adding their touches to the structure.

Interesting Facts

- The word ‘Ieper’ originates from the stream of like name.

- Growing upon the banks of the stream were elms, a tree endemic to the region, that was named ‘Iep’ in the dialect spoken by the Belgae. Today, linguists believe the word derived from Germanic Frisian. Named for the elms growing upon its banks, the river’s name changed over the centuries: ‘Ipre’, ‘Iepere’, ‘Ieper’, ‘Ijzer’, ‘Yser’.

- The Roman settlers named the town ‘Ypra’ after their invasion during the 1st century.

- How many spellings has the town experienced? Can you believe 40! Ypra, Ieper, Ipra, Ipera, Ipre, Ipres, Iprae, Ipera, Iperen, Hypra, Hipra, Ipretum, Hipretum, Ipresnsis, Yppre, Ijper, Yperen, Yper, Yeper, Ypres…………

- After a fire destroyed much of the township in 1241, the decision was made to rebuild all structures in stone.

- 1 in 3 Ieper residents died during the black plague outbreak within the town.

- By 1260, Ieper had a population that numbered 40,000. As comparisons, London’s has been estimated at between 20,000 and 25,000 for the same time period and Oxford’s at approximately 4,200.

- Ieper has a long history of beer making. By 1649 there were 29 breweries, 50 inns and the population was larger than today’s.

Interesting Reads:

Symbolic Menin Gate lions return to site of bloodiest WWI battle _ Flanders Today

Menin Gate_ the history, design and unveiling

Gifgas (Poison gas) _ Flanders Fields bike

Origin of the Name Ieper & history

Information from:

Ypres in War and Peace: Martin Maris Evans. Pitkin Publishing, Pavilion Books

Flanders Today, Saturday 28th September 2019