As with the towns visited to date, Toulouse had that mix of old and new. Buildings no longer cared for rot and decay as, like ancient sentinels, they cracked and crumbled whilst mouldy odours wafted lazily upon air currents from their darkened cellars to tickle the noses of passers – by.

A few rare jewels captured the visitor’s attention.

The Saint Sernin Basilica

As history tells it, this marvel was constructed in honour of the first bishop of Toulouse, Saturnin, who served in a small church – now long gone – during the first half of the third century AD.

During 250AD, the then emperor – Decius – formulated a diktat demanding that all citizens display public respect for the pagan Gods. In this way, they would demonstrate loyalty and support for the state of Rome, which had come under attack from the Barbarian hoards.

Saturnin refused to do so. Ordered to offer a sacrifice, he blatantly defied the command. Retribution was swift and brutal. Feet tied, he was attached behind a bull. Cruelly goaded, the creature at last lost control. In an effort to escape its tormentors, the animal raged through the streets, all the time dragging the soon broken lifeless body of the bishop behind. Fraying, the rope at last snapped free, whilst the bull continued on its way, leaving the battered corpse in its wake.

Placing their lives at risk, two women rescued the man’s remains and buried him.

During the fourth century, the bishop of that time had great deference for Saturnin’s qualities, and searched the bishop’s gravesite until at long last the coffin was unearthed. Being profoundly religious he did not dare move it. As an alternative, a small basilica fashioned from wood was erected above the site.

With the completion of this small monument, the word spread and soon a flow of people commenced arriving to pray upon the ‘relics’. The numbers ever increasing, the fourth century saw the erection of a shrine close by the basilica took place. One century later, the bishop’s remains were exhumed and reburied inside a marble coffin within the new building. Time has seen all three of these buildings long gone and, like the infamous Arc of the Covenant, evidence detailing their position lost in the annals of time.

Of St Sernin, there is minimal documentation and archaeological evidence. The original structure was first mentioned in 844 when churchmen established a group of guardians (Canons) whose sole duty was to keep watch over the Saint’s body. During the eleventh century, the Canons had the current church constructed to replace the former. This massive structure was at last completed in the 1500s.

In 1970, the remains of an apse were uncovered in the current St Sernin Basilica’s crypt, and it is believed to have been part of the previous church.

Since its completion, the Basilica has undergone massive changes to its layout, as demolitions, additions and restorations took place, at last providing those living in the twenty first century with the face it presents today.

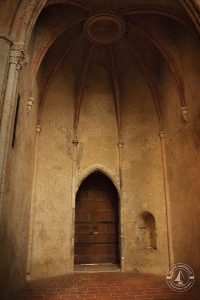

Jacobin Convent

Unlike many church buildings of earlier times, this convent’s history wasn’t lost to the mists of time.

At first glance plain, yet upon a closer inspection a work of intricate beauty. What contrast to the richly coloured, ornate churches that overwhelmed the senses. To date, this has been one our favourite buildings.

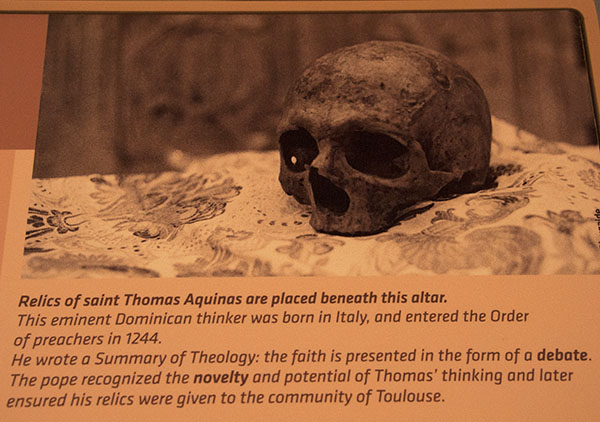

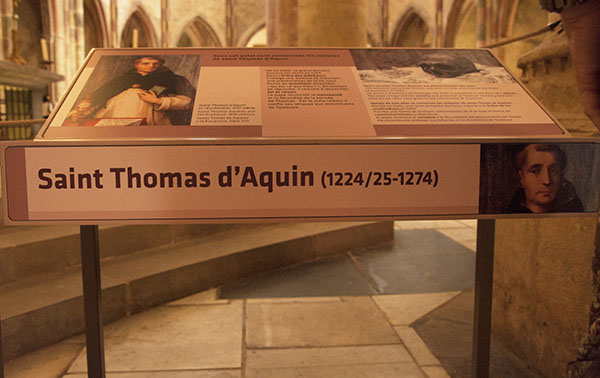

Upon further research into St Dominic who, with the support of the Catholic Church, founded the order of the Dominic Friars in Toulouse in 1217, the reader soon understood why.

The order’s constitution dictated a life where revenue was denounced and the friars lived by begging. Intellectual work came foremost, and there was no obligation to carry out manual labour. Standards were established for the building and maintaining of all their convents. Minimal monies were spent, heights limited, only a single bell installed within the steeple and furnishings expected to be plain.

With a rapid growth in membership, the original convent became unable to house its residents, and the construction of the building seen today commenced.

A donation of 1800 sous enabled the community to purchase two lots of land on which to build their new church. Commenced in 1230, it took four years to construct a rectangular building 22 metres wide, 46 metres long and 13.5 metres high. Based upon a Parisian convent situated on Rue St Jacques, the Toulouse convent took its name from this.

Over the coming years, the order’s role in the church became ever more powerful and its population rapidly increased.

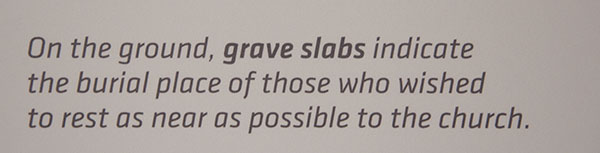

During the mid – 1200s the building underwent numerous extensions. Additional lands purchased enabled the construction of its cloister (garden area) upon the northern face. An extension to the refractory took place, whilst simultaneously, the additions of an infirmary, hostelry and new dormitory occurred. An additional two bays, a pentagonal apse and eleven rectangular chapels all went towards increasing its size to 22 metres x 72metres. Outside, a cemetery was created, and many who assisted with the financing were buried there.

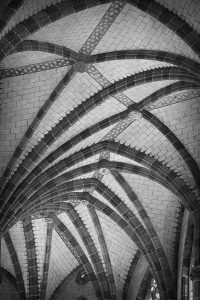

By the late 13th century times had changed. The new architect took a more relaxed view of Dominic’s building regulations and the younger generation, not having known Dominic, were quite happy with this. With the renovation of the churches chevet, came the incredible structure of 28 m high ‘palm tree’, for which the Abbey is best known today. Tall stained-glass windows allowed the light to shine through upon murals that decorated the walls. Demolition also took place as an impressive octagonal seven story steeple and spire replaced the building’s northern chapels.

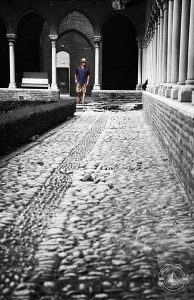

The cloister we viewed had replaced the original in the early 14th century. By that time the church roof consisted of two levels, a massive difference in height of fifteen metres. A teacher at the Abbey bequeathed monies for raising the roof and additional alterations he requested to the abbey upon his death.

The commencement of the 15th century found the Abbey completed, a funerary chapel and the last of the naves completing on its appearance.

Over the past four centuries, the church has not escaped the ravages of time: an earthquake, demolition of sections for the construction of a road that never eventuated, steeple lost, its copper balustrade removed and finally closed for the period of the French Revolution.

These damages were minor compared to the destruction caused by Napoleon’s army during their time of habitation: it was enough to make a person want to cry. A bit of soil upon the floor and cloister raised them to the level of the street. Two wooden floors were placed in the naves creating a warehouse and hayloft, whilst the ground floor was made into a stable. Drinking troughs replaced several pillars, whilst site chapel entrance ways and high windows – of which the stained glassed windows were sadly destroyed (what a crying shame!!!) – were bricked in. All paintings were covered in white wash- what sacrilege –walls built to cover various aspects of the structure, whilst others were totally annihilated – feel like crying about now????

The spoils of war often have a lot to answer for.

At a later date, the refectory found itself used as a riding school whilst another area housed an infirmary. As if that wasn’t enough, further damage occurred to the cloister during years it was used as playground, whilst the wood stove used by art students destroyed the wall murals of St Antonin’s Chapel when the area was used as a classroom.

By the mid – 1860s the building had become severely dilapidated. Exploring the Abbey today, the renovations were such that it was difficult to believe.

Our generations today can thank those farsighted people who worked so diligently between 1865 and the 1980s to restore the Abbey. Over the years, walls were rebuilt, and surprisingly, various missing pieces discovered in unexpected places: for example capitals at la Capiere and sections of the cloister at Mauren’s Scopont castle.

Today, this masterpiece stands proudly, restored as closely as possible to that of its pre – Napoleonic desecration.

Night ride through Toulouse

In a first, we went for a night bike ride through Toulouse and took some night shots. The bright lights of the night provided a new ambience to the atmosphere of the town.

Even Bob had a go taking pics.

The onset of evening was beautiful.

La Capitol, the City Hall, was organized around what had been Henri the Fourth’s courtyard. Today, this was a massive square in which markets were held on a regular basis, and the general populace gathered for a bite and social natter.